It’s a little late for Mothers’ Day but never too late to highlight opinionated women! I’ve noted before how many brilliant women appear in Erasmus’ Colloquies and argued that Shakespeare must have appreciated them: he being the creator of so many sharp-witted and powerful female characters, from Beatrice to Lady Macbeth! For my next few entries I’d like to highlight a few of the strong-willed women Erasmus brought to life. He never once created a dull one. (This and several others are in my book.)

It’s a little late for Mothers’ Day but never too late to highlight opinionated women! I’ve noted before how many brilliant women appear in Erasmus’ Colloquies and argued that Shakespeare must have appreciated them: he being the creator of so many sharp-witted and powerful female characters, from Beatrice to Lady Macbeth! For my next few entries I’d like to highlight a few of the strong-willed women Erasmus brought to life. He never once created a dull one. (This and several others are in my book.)

Written forty years before Shakespeare was born, “Puerpera” (or “The New Mother” or “The Lying-in Woman”), introduces us to Fabulla, a sixteen year who has just had a baby, and Eutrapelus, a portrait painter. Here is the beginning of the colloquy:

Pruerpera translated from the Latin original

Characters:

Eutrapelus, an artist

Fabulla, a new mother, sixteen years old

(This colloquy opens with obscure references to current events of the 16th century, which we’ll leave out here)

Eutrapelus: Honest Fabulla, I’m glad to see you. I wish you well

Fabulla: I wish you well heartily, Eutrapelus. But what’s the matter more than ordinary, that you that come so seldom to see me, are come now? None of our family has seen you this three years.

Eutrapelus: I’ve come to congratulate you on a happy delivery

Fabulla: Congratulate me on a safe delivery if you like, Eutrapelus. Wait to congratulate me on a happy one when you see him grown into an honest man.

Eutrapelus: Dutifully and truly spoken, my Fabulla.

Fabulla: I’m nobody’s Fabulla except Petronius’

Eutrapelus: Yes, you obey only Petronius, but you don’t live only for him, I dare say. But I congratulate you further for having produced boy.

Fabulla: But why do you think it’s better to have a boy than a girl?

Eutrapelus: Nay, Petronius’ Fabulla (for now I’m afraid to say my Fabulla), you tell me why you’re glad to have boys rather than girls.

Fabulla: How other women may feel I don’t know; for my part, I’m pleased now to have a boy because it was God’s will. Had he willed me to have a girl, I would have been pleased too!

Eutrapelus: Do you imagine God has so much leisure that he attends a woman in labor?

Fabulla: What could he better do, Eutrapelus, than preserve by propagation that which he has created?

Eutrapelus: What could He better do, my good woman? On the contrary, if he weren’t God I don’t think he could get through so much business. King Christian of Denmark, a devout partisan of the gospel, is in exile. Francis, Kin of France, is a prisoner of the Spaniards. What he thinks of this I don’t know, but surely he’s a man of worthy of a better fate. The Emperor Charles is preparing to extend the boundaries of his realm. Ferdinand has his hands full in Germany. Bankruptcy threatens every court. The peasants raise dangerous riots and are not swayed from their purpose, despite so many massacres. The commoners are bent on anarchy. The Church is shaken to its very foundations by menacing factions. On every side the seamless coat of Jesus is torn to shreds. The vineyard of the Lord is now laid waste not by a single boar but at one and the same time by the authority of the priests and their tithes. The dignity of theologians, the splendor of monks, is imperiled. Confession totters, Vows reel. Pontifical ordinances crumble away. The Eucharist is called in question, Antichrist is awaited. The whole earth is pregnant with I know not what calamity. The Turks conquer and threaten all the while and there’s nothing they won’t ravage if their undertaking succeeds. And you ask what could He better do? No, I think it’s time for him to look out for his kingdom!

Fabulla: What men think is most urgent may seem insignificant God. But let’s exclude God from this cast, if you will. Tell me. What are your reasons for believing it is more blessed to have a lad than a lass?

Eutrapelus: It’s a duty to consider this the best because God, who is beyond question best, gave it. Now if God gave you a crystal cup, wouldn’t you thank Him heartily?

Fabulla: I would.

Eutrapelus: What if He gave you one of glass? You wouldn’t thank Him as much, would you? – But I think I’m a bother rather than a comfort arguing these questions with you.

Fabulla: Not at all! Fabulla’s in no danger from fables. I’ve been in bed a month now and I’m strong enough to fight.

Eutrapelus: Then why don’t you fly out of your next?

Fabulla: The king forbade.

Eutrapelus: King who?

Fabulla: A tyrant, rather.

Eutrapelus: Who, I ask?

Fabulla: In a word, custom.

Eutrapelus: Ah, how many unjust commands that king makes! — Let’s go on discussing crystal and glass then.

Fabulla: I suppose you think man is naturally better and stronger than woman.

Eutrapelus: So I believe.

Fabulla: On the authority of men, to be sure. Men aren’t therefore longer lived than women? Not immune to disease?

Eutrapelus: Not at all. But they generally excel in strength.

Fabulla: But they themselves are excelled by camels.

Eutrapelus: Well… but man was created first.

Fabulla: Adam was created before Christ. Is he better? And artists usually surpass themselves in their later works.

Eutrapelus: But God made woman subject to man.

Fabulla: A ruler’s not better merely because he’s a ruler. And it’s the wife, not the female, who is subject. Again, the subjection of the wife is such that, though each has power over the other, nevertheless the woman is to obey the man not as a superior but a more aggressive person. Tell me, Eutrapelus, which is weaker: the one who submits to the other or the one to whom submission is made.

Eutrapelus: I’ll yield to you in this…..

And who wouldn’t yield? This colloquy continues with Eutrapelus lecturing Fabulla on the wisest way to raise a healthy baby and getting an earful in response. In the end, Eutrapelus is able to convince the argumentative Fabulla to nurse her own baby and not leave that to a wet nurse, which defied the custom of the time. Erasmus often questions “custom.” This is one example of Erasmus’ wisdom that seems so contemporary today.

(I left intact the long list of upheavals in early 16th century Europe that Eutrapelus puts in juxtaposition to Fabulla’s domestic situation because it’s such a vivid glimpse of that time.)

You can order it directly from Routledge:

You can order it directly from Routledge: I’m delighted that many friends and colleagues will be joining us on

I’m delighted that many friends and colleagues will be joining us on  Kate Zoeger is loving my book! Here’s what she has to say:

Kate Zoeger is loving my book! Here’s what she has to say:

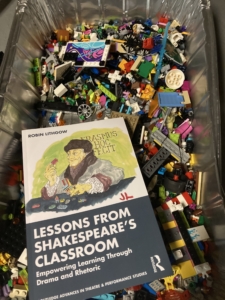

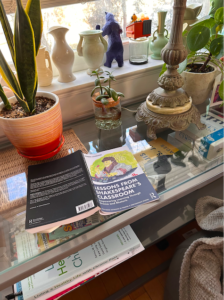

Here are a few images sent to me by readers enjoying my book, “Lessons From Shakespeare’s classroom: Empowering Learning Through Drama and Rhetoric.”

Here are a few images sent to me by readers enjoying my book, “Lessons From Shakespeare’s classroom: Empowering Learning Through Drama and Rhetoric.”

The book’s setting, in a box of legos, is a humorous nod to my last chapter, the one on the research: “The Lego Snap of Learning.”

The book’s setting, in a box of legos, is a humorous nod to my last chapter, the one on the research: “The Lego Snap of Learning.”