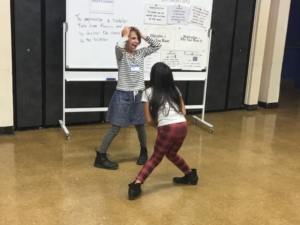

Students at Westminster Elementary drama class explore a Mexican trickster story, “The Rabbit and the Coyote”

My greatest joy during the years I was with the Arts Education Branch in the Los Angeles schools was observing our theatre and dance teachers light up the minds of children. It drove me to distraction, to see what I saw, knowing that access to regular instruction in the performing arts is not available to every child, every day. During my tenure with the Arts Branch I went to dozens of state and national conferences and symposia on arts education where the enthusiasm among arts teachers was palpable; but in the broader field of educators, the general malaise about the performing arts in pedagogy grated on my mind. That is what compelled me to write my book.

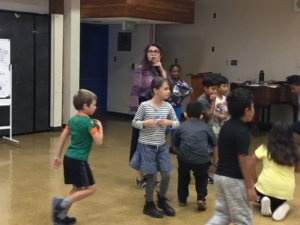

Theatre teacher Afsaneh Boutorabi with third grade students

This is the twentieth year of the Elementary Arts Program that my colleagues and I started in 1999, adding dance, theatre, and visual arts to the existing music programs in the schools. It’s incredibly gratifying, today, that both my granddaughter and my great niece are kindergarteners in LAUSD schools that embraced the arts program early on and are receiving drama lessons from fabulous teachers that I hired twenty years ago. But that is just the luck of the draw. My delightful, expressive, creative grandchildren and their peers in other cities in other states are in fine public schools with great teachers, but they don’t get regular instruction in drama or creative movement, and that breaks my heart.

There is a massive amount of research that proves beyond any doubt that the performing arts do much to foster cognitive skills: curiosity, inquiry, and reflection. The researcher James Catterall often said he would stake his life on the bet that daily incorporation of drama into the classroom would increase verbal skills and those test scores that, sadly and misguidedly, are the holy grail of every district. (I’ve expressed my personal view of our testing culture vs. arts education in a previous post.) When used by skillful teachers they are also roads into deeper and more lasting learning in subject matter content across the curriculum.

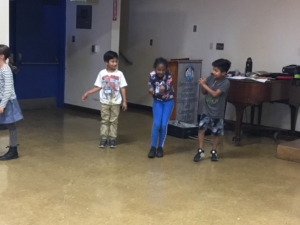

Students planning possible solutions to the trickster story

Here’s the problem I’ve found with research: As time consuming and effortful it is to complete and publish credible research, it is even more difficult to get anyone to pay attention to it! (Unless, of course, there is a significant economic benefit to be proven. Thus the tsunami of testing that school children are experiencing now.)

Students create beginning, middle, and ending tableaux of the story

Here I’ll just summarize a couple of my favorite research stories. First, the REAP Report that came out of Harvard’s Project Zero about twenty years ago. REAP stands for Reviewing Education and the Arts Project. This study did not conduct its own investigations, but instead analyzed the results of hundreds of research studies carried out over the past half century, hoping to find irrefutable links between classroom arts and academic scores. In the executive summary the editors caution the reader, pointing out that 1.) It is difficult to establish irrefutable links because of the infinity of variables in education and 2.) It is a shallow task. It is shallow because it implies that academic achievement in the three Rs is the only reason that the arts should be taught. In fact they needed this caveat because in some ways the project was a disappointment. They were only able to find irrefutable links in two of the ten areas they had identified. However, significantly, they did find a strong link between classroom drama and verbal test scores. Again, statistically, it was an irrefutable link, and, what was even more important, the increase in achievement was transferable from subject to subject. So theatre was the winner in that particular study.

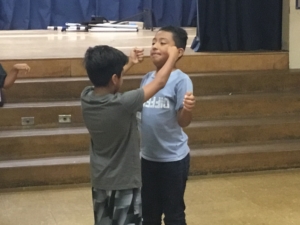

Student “sculptor” creates a frozen statue for his tableau

I’m not sure if the other report was ever published, but I’m looking into it. The brilliant linguist Shirley Brice Heath, at Stanford, became interested in arts education because of her observations of verbal development in children. Several years ago she was a speaker at a symposium on arts education that we presented at the Getty to school administrators. She described a study that was ongoing at the time. She told us that she had research assistants who went into classrooms covering subject areas across the curriculum, and that all they did was clock the seconds that students in each class made direct eye contact with the lesson—either with the instructor or with the task assigned. Obviously, eye contact is not the only indicator of attention, but it is one that is easily observable and measurable. In eye contact alone, attention in arts classes far exceeded that in any other subject. Indeed, student attention was “off the charts” in comparison. Students were attentive and engaged, and engaged learners are open to new ideas that mesh with the patterns of knowledge they already have inside of themselves. Their learning is thus enhanced and enduring.

Research in the impact of the arts in learning is limited by the fact that funders, so far at least, are mainly interested in accountability as measured by test scores. Research investigations looking for “soft data,” such as school attendance, teacher retention, and evidence of improved school morale (e.g. joy) definitely show positive results but get far less attention. Another perhaps more fertile area of research is the booming field of neuroscience and cognition, but I will save that for a later post.

Bravo, Robin!

The Play’s the Thing indeed!

The Winter’s Tale

June 18th-20th,

El Portal Theater

North Hollywood, CA

Hi! Thanks Rafe. You would know!!!!

Can’t wait for your next post………Love tim

There is nothing more gratifying than seeing the children engaged in the arts. Traveling from school to school throughout LAUSD as the dance specialist I had the opportunity to see children dancing, singing, acting, and creating works of art with all kinds of materials. I didn’t need statistics or long term studies to prove that no other subject seemed to engage students like the arts. When children were given the opportunity to collaborate and create it seemed as if differences flew out the window and students became focused on completing their group project, be it a simple movement problem, visual arts assignment, enhancing a research project with some artistic genre, or creating a presentation for the school talent show that included dancing, singing, and acting. It saddens me that we are still fighting to see that every single child has daily access to quality arts education.