When and why did the teaching of rhetoric in grammar schools end?

When and why did the teaching of rhetoric in grammar schools end?

Following up on two previous posts on Shakespeare’s education in rhetoric (Collaborative Classroom Hilarity and What’s With All the Rhetoric), I don’t have a concise answer to this question, but I’ve been searching for one. (I once typed the question into Google and got some hilarious answers, some of which I quote in my book.) If any of my readers want to join in this exploration I’d be overjoyed.

One thing I do know is that at the time of Samuel Johnson, rigorous training in rhetorical speech and writing was still alive and well, and its use was the subject of much deliberation. I’ve just finished The Club, by Leo Damrosch and found plenty of evidence to support this. It’s a terrific read. It’s about the literary club founded by Joshua Reynolds and Johnson, which met weekly all through the second half of the 18th Century. I had to brush up on my knowledge of the literature and society of that era and all of the esteemed members of The Club. I haven’t read Johnson or Boswell since college, have only read a few speeches by Burke, have never read Gibbon, and skipped economics so, to my shame, am only peripherally aware of Adam Smith and The Wealth of Nations. Of course I’ve gazed at plenty of luminous paintings by Joshua Reynolds but knew very little about the man himself. But in addition to filling in some gigantic holes in my knowledge of that era, scattered through the book there is enough there to tell me that all of those brilliant writers, orators, and artists were well educated in rhetoric.

And that means that there was yet another “Generation of Genius” to emerge from the humanist education designed by Erasmus!

Damrosch does not offer any information about 18th Century education, but writing and speaking style was clearly a hot topic at the time, and that is certainly a reflection of training. A lot of attention was paid to it. By the time of Samuel Johnson, our language had developed distinct rhetorical styles. Here Damrosch describes the happy period and the periodic style:

Samuel Johnson

“Of course style is much more than words alone, whether long or short. In one of the essays Johnson describes the challenge of shaping each sentence and paragraph into a compelling whole: ‘It is one of the common distresses of a writer to be within a word of a happy period, to want only a single epithet to give amplification its full force, to require only a correspondent term in order to finish a paragraph with elegance, and make one of its members answer to the other; but these deficiencies cannot always be supplied; and after a long study and vexation, the passage is turned anew, and the web unwoven that was so nearly finished.’

“Johnson refers to ‘a happy period’ because his style is the kind that used to be known as periodic. When we use the word ‘period” we mean simply the punctuation mark. But in traditional rhetoric it meant the whole interconnected structure of clauses that brings us to that conclusion. ‘The periodic stylist, Richard Lanham says, ‘works with balance, antithesis, parallelism, and careful patterns of repetition. All of these dramatize a mind which has dominated experience and reworked it to its liking.’”

I can’t think of a better description of the struggles experienced daily by every writer in our language struggling with the arc and structure of the sentence, the paragraph, the chapter, the book. In great writing you can really see the rhetorical training that goes into the “balance, antithesis, parallelism, and careful patterns of repetition.”

James Boswell

Johnson’s writing was very much in the classic tradition. Boswell’s style was totally different, but also much appreciated. In fact, Boswell in his day was pretty much a total lightweight: an alcoholic and a womanizer who never attained any significant success either as a lawyer or a politician, but his colorful and chatty writing style made him a delight to read and saved him for posterity. Each of the early members of of The Club was held in great esteem for their literary abilities, and each had his own highly developed and distinctive style.

Johnson’s Dictionary of the English Language did a great deal to further the evolving plasticity and expressiveness of our amazing English language. To quote again:

“On the two hundredth anniversary of his death, the Times declared, ‘The chief glory of the English is their language; and Johnson’s Dictionary, the only one in any language compiled by a writer of genius, had a lot to do with its rise to glory…..

“In France, the Académie Française was also preparing a dictionary, with the intention of fixing the ‘correct’ meaning of every word for all time. Johnson, altogether differently, invented the mode of defining words that was later carried forward by the Oxford English Dictionary. He wanted to show all the ways they had ever been used, and to include examples from earlier writers that would illustrate their usage in specific contexts.”

So Johnson recognized the richness of the mutability of meanings of words in our language, which has done so much to make it a such a muscular, nuanced, and infinitely inventive mode of expression. Shakespeare and his peers at the turn of the sixteenth century gloried in their freedom with their newly fashionable and much loved vernacular, which, because it had been essentially a street language for centuries, had virtually no rules. It was a malleable material with which to create wonders. Instead of ossifying our language with rules, as the Académie Française has attempted to do with French, Samuel Johnson continued to encourage its adaptation to his age and ages to come by showing how it was evolving in its ability to express new ideas in new ways.

As for the other genius members of the club—

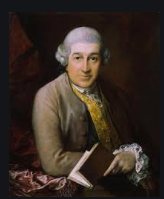

David Hume:

David Hume

“A modern editor of Hume’s History of England says that Hume’s style ‘is the fastest and smoothest vehicle in historical literature.’ That may be the style most appreciated today, but it’s not Gibbon’s, any more than it was Johnson’s. Their style was periodic, and their unit was the fully crafted paragraph. “It has always been my practice,” Gibbon says, “to cast a long paragraph in a single mould: to try it by my ear, to deposit it in my memory, but to suspend the action of the pen until I had given the last polish to my work.”

Adam Smith:

Adam Smith

“After giving public lectures in Edinburgh, where he had no academic post, in 1751 Smith became Professor of Logic and Metaphysics at the University of Glasgow. A year after that he was elected Professor of Moral Philosophy, and he did indeed think of himself as concerned with human behavior in all its aspects. His lectures that Boswell heard were on rhetoric, by which was meant not just literary style, but persuasive public language in the tradition of Cicero. The emphasis was on language as a social instrument, and Smith recommended a straightforward plain style instead of the elaborate figures of speech that older rhetoricians liked to use.”

Edmund Burke:

Edmund Burke

“Most of the 558 members of the House of Commons never dreamed of making speeches, but star orators could hold forth for hours at a time. Persuasive eloquence was essential, and so was quickness in cut and thrust debate. Burke excelled at both. And although the debates weren’t supposed to be reported in the press—that was why Johnson had to invent them in his journalistic days—the speakers could always publish their own speeches afterward, which Burke regularly did in pamphlet form.”

David Garrick

And then, of course, there was the actor and producer David Garrick who changed the course of theatre in England. And, there were a host of smart, published writers who were not members of The Club, some of them women!: Fanny Burney, Hester Thrale, Elizabeth Montequ, the playwrights Hannah More and Elizabeth Griffith, and on and on.

So, once I get Good Behvior and Audacity: Humanist Education, Playacting, and a Generation of Genius published, maybe I’ll have to start gathering material for another book, proving the point again. I’ll repeat it again: simple adjustments to modern pedagogy, emphasizing performing arts and elevated oral and written language, could nurture our own “Generation of Genius.”

All of the above quotes are excerpts from: Leo Damrosch. “The Club.” iBooks. https://books.apple.com/us/book/the-club/id1455106450Excerpt From: Leo Damrosch. “The Club.” iBooks. https://books.apple.com/us/book/the-club/id1455106450