The Tudor Tattle: Pastime with Good Company

The day of the old morality plays ended in 1514, when the young King Henry VIII stood up in the middle of one, yawned, and walked out of the room. Two years earlier, during a celebration of Twelfth Night (the holiday, not the play), Henry’s Sergeant of the Revels had introduced a brand new style from Italy: the Meskaler: “called a masque, a thing not seen afore in England.” The sets, the dress, the colors, the music, the wit, and especially the dance that the noble observers always joined at the end, all imported from the seat of the Renaissance, quickly displaced the old religious dramas that had dominated English theatre for centuries. This new style, mixing music and dance with interludes of dialogue, had a huge impact on theatrical productions during Henry’s reign.

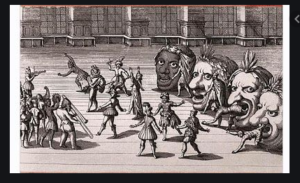

It was the in the “interludes of dialogue” that the Children of the Chapel had their big opportunity. The masques were lavish and they involved unbelievably elaborate pageant wagons that would put our Rose Parade floats to shame. Here’s a description of just one: “adorned with purple and gold, having branches wrought of roses, lilies, marigolds, gillyflowers, primroses, cowslips, and other kindly flowers, with an orchard of rare fruits, all embowered by a silver vine bearing 350 clusters of grapes of gold. It contained thirty persons, and its great weight broke the floor as it moved up the hall. On the sides were eight minstrels with strange instruments, and on the top, the Children of the Chapel singing.” At least one of wagons was said to be pulled by lions and antelopes! (Really?! I know that is hard to imagine, but that’s in the description. They may have been huge disguises manipulated by several bodies?) Since they where heavy enough to crack the tile flooring at court, the light bodies of the boys were an asset, and their trained voices made them natural candidates for the interludes. Indeed, before they were called actors, these young Thespians were called “interluders.”

Eventually there were two major boys’ companies who entertained the aristocracy, providing most of the theatricals at court for the first eighty years of the 16th century. They were the Children of the Chapel Royal and the Children of St. Paul’s. There were other companies in the provinces that came and went, playing for the great houses of the dukes, earls, viscounts, and lords, but because of the meticulously kept royal records we have the most information about the Chapel and St. Paul’s boys. Researching them I relied heavily on two books written early in the last century: The Evolution of the English Drama up to Shakespeare by Charles William Wallace and The Child Actors by Harold Newcomb Hillebrand. Very little attention has been paid to them since, which, if Wallace and Hillebrand are correct, is kind of astonishing. Both of them make a convincing argument that the Golden Age of Elizabethan theatre would never have happened without them!

Tudor Musicians at Court

Both Wallace and Hillebrand convincingly show that the immense popularity of child actors that peaked in the 16th century was not a passing fad. The use of children in the performance of music and drama had deep roots going back hundreds of years. But because of royal favor and the historic currents that favored theatrical entertainments, it reached its full flowering during the Tudor age. There was a lot of money to be thrown around, and the very best dramatic talent in the realm could be had for top dollar. A long list of choirmasters and dramatists writing for the boys companies includes John Heywood, Nicholas Udall, Richard Edwards, Richard Ferrant, William Hunnis, John Lyly, Robert Greene, George Peele, Christopher Marlowe, George Chapman, John Marsden, John Webster, Ben Jonson, Anthony Munday, Thomas Dekker, and Thomas Middleton. In other words, just about every playwright of any note, all the way through the early Jacobean period, wrote occasionally—and lucratively—for boy actors. Even the Earl of Oxford, the favorite candidate of the Shakespeare deniers, wrote for them. It would have been beneath his social status to write for the public theatres, but the boys’ companies were private and had a better class of clientele.

Furthermore, if the highly credible and persuasive theory that a boys’ company first performed Love’s Labors’ Lost is correct, the list would include William Shakespeare himself!

Choirmaster playwrights ransacked Plautus, Terence, Chaucer, Aesop, classical history, and mythology for story fodder. Some of the plays were clearly allegorical and seem to come straight from debate topics for schoolboys, many suggested by Erasmus, such as one performed for the Revels in 1527, in which dialogue was performed between riches and love, arguing which one was more valuable in choosing a spouse. The rhetorical device of prosopopoia (impersonation of an abstract idea) was very much in evidence in boy characters impersonating every known variety of virtue and vice, fortune, poverty, divine wisdom, the muses, the worthies, the seasons, the elements, the sun, the moon, and all manner of abstractions. The titles seem to be an endless series of Somebody and Somebodys or Something and Somethings: Appius and Viginia, Damon and Pythias, Troius and Pandor, Palaemon and Arcyte, Cloridon and Radiamante, Predor and Lucia, The Pardoner and the Friar, Sir Clyomon and Sir Clamydkes, John the Husband and Tyb the Wife, Loyalty and Beauty, Wit and Will, Jack and Jill, etc.

The fact that so many of the scripts were discarded or lost after they were performed should not be a reflection on their quality, only on the ephemeral nature of the culture of the court. There are indications that many of the now forgotten entertainments were excellent. Contemporary audiences raved about them. As the century wore on and as the plays became more sophisticated in style and structure, many of them did survive the neglect of time. Some were revived by popular demand, re-staged for the public by grammar school boys, and some were published because their auditors and authors valued them. But it was not until the first half of the reign of Elizabeth that plays written for boys took on an artistry of their own, especially those of John Lyly.

Part 3 will look at the period of the boys’ companies during Elizabeth’s reign, when they began to have competition from the major men’s companies. That is when the style they represented (that of the court) merged with the styles developing beyond the palace walls, and morphed into the great comedies, tragedies, and histories we still admire today.

Riveting, and written well. Looking forward to reading the next installment.